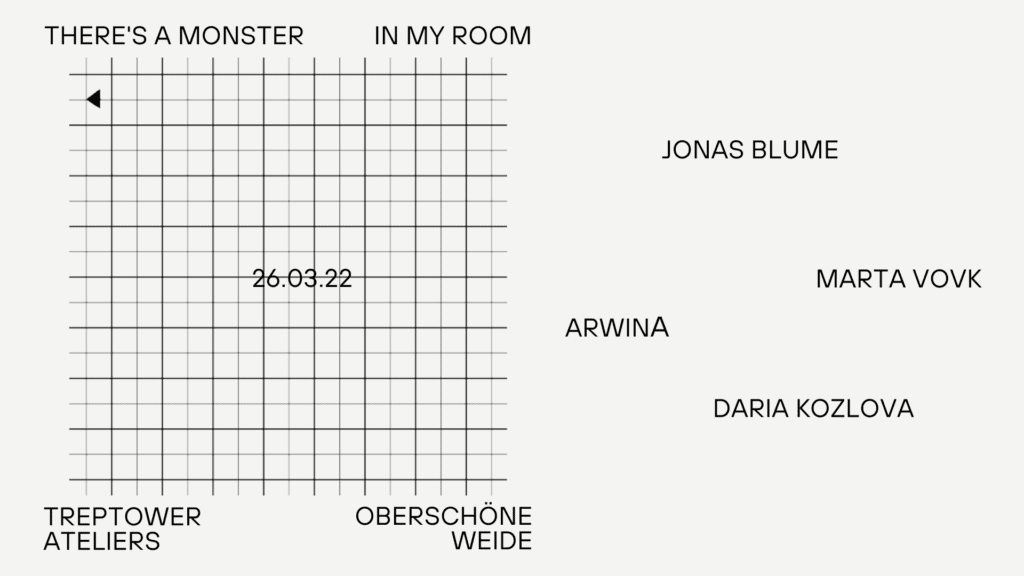

there’s a monster in my room

26.03.2022, 4 pm – 3 am Treptow Ateliers As part of the exhibition “Opening Hours” by Fünfter Löffel e. V.

Unlock the door. Sit on the couch. Switch on the console. The familiar start up sound blasts. Grab the controller. Start the game. The room is darkened. Coloured light emits from behind the screen. Red green purple blue. The night is young, and in the world of games the clock ticks differently anyway. Steadily repeating its sped up cycle. Slow motion and superhuman speeds are the status quo. The caffeine kicks in, the next round, next level, next opponent, next quest demands attention. Death and life are only a few keystrokes apart. Rebirth is a given. Finally back. No matter whether it’s a chaotic children’s room, a lovingly decorated man-cave or a highly professional streaming studio: in the gaming room, you’re usually alone. The bulky gaming chair at the desk only leaves room for one person, the curved monitor only unfolds its full effect from one angle. Nevertheless, gamers are not lonely: in game or in chat they are in constant exchange, often also in competition. Numerous accessories promise better performance: gaming mice, keyboards, chairs, tables, headsets, even specialized energy drinks or snacks are available. What role does gaming play in our society? If we follow Johan Huizinga’s Homo ludens, playing is the basic constitution of man – only through play does he develop culture and meaning. According to him, the space of play is a space in which the framework of action is already fixed – but within the framework, man can try himself out. Without play, man would not be who he is today. Progress is told from the now to the future, but the future must be tested in play. The playing human being is thus essential for human beings and their future. But the question arises whether gaming follows the idea of Homo ludens? What at first glance appears to be a lonely, isolated activity removed from real life, is in fact much more. The gaming room can function both together with friends or alone. Interaction takes place both in the game and next to each other on the couch. It is a space that functions both two- and three-dimensionally, that is both corporeal and incorporeal. But it is always also a place that reproduces societal power dynamics, because “the actual subject of the game […] is not the player, but the game itself” (Gadamer). Playing always means being played. And the more seamlessly the game conveys itself to the human being, the more invisible the being-played becomes. The only question is how playing and being played are evaluated. Can the gamer use the possibilities of the game to reformulate their existence and create utopias? Or are they being played, every step taken already thought out and every immersion in another world following the same monotonous principles? We will get to the bottom of these questions. We open the solitary gaming room to a large audience. The works shown deal with gaming or use video games as a medium. In Rhythm Zero Los Santos, Jonas Blume follows in the footsteps of Marina Abramovic’s performance, in which the audience was able to use a variety of objects on her for six hours. The performance escalated and almost ended with her death. Blume re-enacts this performance in the world of GTA Online, where excessive violence is part of the game. How do the players react when there is no counter-reaction? How do we view the behaviour in online games when we put the controller down? In their current project, the role-playing simulation Limboship, ArwinA and Daria Kozlova depict situations that people with migration status have to experience every day: from discrimination and bureaucratic harassment to police violence and deportations. Limboship is played in first-person perspective, focusing on experiences international students have to go through at the National Immigration Office, based on actual events, testimonies and interviews. Marta Vovk repeatedly uses brand logos in her works and combines them with characters from anime and children’s series. MNST confronts the viewer with the oversized logo of the energy drink Monster, which has become an integral part of the gaming scene. Detached from the product, the brand emblem reminds us that behind hobby and community lies an industry worth billions that profits from the brand cult and the loyalty of gamers.

Artists

Jonas Blume ArwinA & Daria Kozlova Marta Vovk

Marta Vovk: MNST, 2018Jonas Blume: Rythm Zero Los Santos, 2019Foto © Patrick Mahr

Marta Vovk: MNST, 2018Foto © Patrick Mahr

ArwinA & Daria Kozlova: LIMBOSHIP, ongoingFoto © Patrick Mahr

ArwinA & Daria Kozlova: LIMBOSHIP, ongoingFoto © Patrick Mahr